[ad_1]

BIOGRAPHICAL EXPLORATION

Meditation, Health and Scientific Investigations: Review of the Literature

Cynthia Vieira Sanches Sampaio1,2 • Manuela Garcia Lima1 •

Ana Marice Ladeia1

Published online: 25 February 2016 � Springer Science+Business Media New York 2016

Abstract A growing number of people are seeking health recovery treatments with a holistic approach to the human being. Meditation is a mental training capable of producing

connection between the mind, body and spirit. Its practice helps people to achieve balance,

relaxation and self-control, in addition to the development of consciousness. At present,

meditation is classified as a complementary and integrative technique in the area of health.

The purpose of this review of the literature was to describe what meditation is, its practices

and effects on health, demonstrated by consistent scientific investigations. Recently, the

advances in researches with meditation, the discovery of its potential as an instrument of

self-regulation of the human body and its benefits to health have shown that it is a

consistent alternative therapy when associated with conventional medical treatments.

Keywords Health � Integrative treatment � Meditation � Spirituality � Well-being

In the East, meditation is an ancient practice, developed by various traditions to broaden

consciousness and seek health. Ancient texts, with reference to the Indian Ayurvedic

system of medicine, demonstrate that this practice formed part of medical procedures used

for the recovery and maintenance of health that go back further than 3000 years ago

(Carneiro 2009), whereas, in the West, the tradition of meditation is usually linked to

religious experiences, especially Christian with a Catholic or Protestant connotation.

However, as from the 1970s, Western groups and movement in contact with Oriental

experiences opened themselves to understanding and make use of meditation—without a

& Cynthia Vieira Sanches Sampaio cysampaio@gmail.com

1 Bahiana School of Medicine and Public Health, Bahia Foundation for the Development of Sciences, FBDC, Salvador, Bahia, Brazil

2 Centro Médico Iguatemi, Av. Tancredo Neves, 805-A, Sala 301, Caminho das Árvores, 41820-021, Salvador, Bahia, Brazil

123

J Relig Health (2017) 56:411–427 DOI 10.1007/s10943-016-0211-1

specifically religious nature—as a resource for the practice of a healthy lifestyle and even

for the cure of psychological behavior patterns, which of themselves act on the general

health of each individual.

The aim of the present study is to evaluate meditation as a useful and necessary resource

for seeking and practicing a healthy lifestyle, based on quieting the mind, reducing stress

and achieving inner harmony. This implies the better relationship of an individual with the

world outside.

In the discourse that follows in this article, a description is given of what meditation is,

its practices and effects on health, revealed by consistent scientific investigations.

Meditation

The word meditation, which expresses the practice of meditating, is derived from Sanskrit,

traditional language of India, from the word dhyana, which means attention, contempla-

tion. The exercise of meditation is processed by a large variety of activities that range from

techniques to promote relaxation through to exercises performed with objectives that are-

broader in scope, such as intensification of the feeling of wellbeing (Lutz et al. 2008). It

also includes breathing techniques, repetition of sounds and/or observation of the process

of thought to focus attention and promote a state of self-awareness and inner calm (Canter

2003).

There are different practices of meditation—those that specifically go through religious

traditions, those that seek connection with spirituality without religious connotation and

those that propose to be a purely mental training, unconnected to a spiritual proposal

(Menezes et al. 2011).

The central point common to the numerous practices consists of temporarily with-

drawing attention from the outside world and thoughts related to it, in order to focus on the

chosen theme of meditation (Servan-Shreiber 2008). The common key to all the practices

is silencing and harmonization of thoughts and judgments bubbling within each person.

Meditation is based on control of attention.

Studies and researches about meditation in the area of health have led to the need for an

operational definition for this term. A group of researchers established some elements as a

parameter for a procedure to be characterized as meditation, composing a definition

accepted in the scientific medium. These elements are as follows: the use of a clearly

defined technique; production of muscle and psychic relaxation with reduction in logical

thought; it must necessarily be a self-induced state; and developing the capacity to

maintain the focus of attention on a certain point that functions as anchor (Cardoso et al.

2004).

For the majority of researchers, there are two general types of meditation: concentration

meditation and mindfulness meditation (Lutz et al. 2008). The former emphasizes the need

for attention focused on an object, and to sustain this process until the mind attains quieting

of thoughts. Its continuous practice produces relaxation and mental clarity

(Krisanaprakornkit et al. 2006). Mindfulness meditation is directed toward the opening of

perception of contents that emerge in the mind, without the individual judging or reacting

to his/her own thoughts and emotions. This technique favors the undoing of previous

conditioned behavioral patterns, making it possible for the individual to create new

strategies for coping with the events of life (Krisanaprakornkit et al. 2006). There is also a

third type of meditation, denominated by some authors as the contemplative type, which

412 J Relig Health (2017) 56:411–427

123

integrates the two previously mentioned types, stimulating both the capacity to focus and

to open oneself (Menezes et al. 2009).

Meditation Recognized by Scientific Investigation as a Resource for a Healthy Life and Cure

The scientific researches listed revealed how much meditation has to offer for attaining a

healthy lifestyle and as a resource to seek cure in an integrative practice of medicine, in

which all the dimensions of the human being are recognized and taken care of.

Despite its practice, each type of meditation identified above, in its own way, offers a

possibility of entering into a state of inner coherence, which favors the integration of all the

biological rhythms and harmonizing functions of the body (Servan-Shreiber 2008). Apart

from this, the aim of the different types of meditative practices is to change the flow of

thoughts, generating new patterns of behavior and awareness (Danucalov and Simões

2006).

When producing an altered state of consciousness, meditation facilitates the metacog-

nitive mode of thought, making it possible to attain the perspective of behavioral cognitive

benefits and healthy psychological functioning (Krisanaprakornkit et al. 2006; Menezes

et al. 2011; Willis 1979).

The initial researches with meditation investigated its effects on human physiology.

Robert Keith Wallace, of the University of California, one of the pioneers of this type of

investigation, in 1970 conducted a classical study that was published in the prestigious

journal Science (Wallace 1970). This study found that during meditation, a reduction

occurs in oxygen consumption and cardiac frequency, and an increase in galvanic resis-

tance of the skin. Furthermore, the electroencephalogram showed a predominance of alpha

waves, thus it was concluded that these physiological alterations were compatible with

changes in autonomic activity, indicative of reduction in sympathetic activities, and

therefore, meditation could have applications in clinical medicine (Wallace 1970).

In the following year, Wallace et al. (1971) conducted a new clinical trial with a larger

number of subjects and with a similar objective. In addition to confirming the previous

results, they identified a reduction in respiratory frequency and elimination of CO2, as well

as a reduction in pH and arterial lactate (Wallace et al. 1971).

These findings encouraged other researchers and showed that during the practice of

meditation, the following occurred: diminishment of cardiac frequency, slower respiration,

reduced electrical conductivity of the skin, reduction in blood lactate, variations in EEG

frequency. In addition, it was verified hormonal variations, modifications in the concen-

trations of innumerable neurotransmitter substances, reduction in body temperature,

alteration in the senses and perceptions, among others, indicating an increase in

parasympathetic activity (Danucalov and Simões 2006).

These physiological changes characterized a state of relaxation and enabled some

understanding to be gained about how meditation operates in the body. In addition, the

relaxation and reduction in stress and anxiety, which are affirmed as results of meditation,

may bring about prophylactic and therapeutic benefits to health (Canter 2003).

Later researchers, with the use of sophisticated equipment, in studies that used a variety

of styles of meditation, showed that in a general manner, this practice could activate areas

of the brain associated with well-being (Davidson 2003), regulation of the emotions (Tang

et al. 2009) and the capacity to sustain attention (Lutz et al. 2009).

J Relig Health (2017) 56:411–427 413

123

In addition, the scientific investigations signaled that the brain dynamics in those who

meditate for many years is different from the brain dynamics of those who do not meditate

(Lutz et al. 2004). Furthermore, they indicated that irrespective of the technique used, it is

a mental training that acts on cerebral functions affecting the manner in which the stimuli

are processed and perceived, thereby helping to undo conditioned behaviors (Allen et al.

2012; Kozasa et al. 2012; Newberg et al. 2001; Singh et al. 2012; Slagter et al. 2007).

At the same time, other researches revealed that meditation, in addition to producing

neuroendocrine and neurochemical effects, which modified the brain activity and meta-

bolism of the individual, may be associated with structural alterations in areas of the brain.

A study with magnetic resonance (Lazar et al. 2005) compared the brain of experienced

meditators with the brain of non-meditators. She found significant difference in the

thickness of the cerebral cortex of the meditators, which was larger in the insula and

prefrontal cortex, brain regions in which attention and the emotions are concentrated.

This study suggested that meditation might generate changes in the brain favoring

improvement in the person’s cognitive and emotional functions, in addition to retarding

brain aging. However, because it was a cross-sectional study, it was not possible to

demonstrate causality.

More recently, a controlled longitudinal study (Hölzel et al. 2011), aimed to investigate

changes in the brain through the practice of meditation, proved that this activity increased

the gray matter in certain regions of the brain, altering its structure.

During the study, sessions of magnetic resonance were performed of the brain of all the

participants before and after the period of practices. The initial exams showed no differ-

ence between the intervention and control groups. However, the resonance exams per-

formed after 30 min of meditative practice daily, for 8 weeks, showed increase in the

concentration of gray matter of the left hippocampus, posterior cingulate cortex, tem-

poroparietal junction and cerebellum in those who practiced meditation, in comparison

with those who did not meditate. These regions of the brain are associated with processes

of learning, memory, regulation of emotions and empathic capacity.

In spite of the innumerable researches conducted over the last few decades about the

effects of meditation on the human body, yet little is known about the neural and biologic

mechanisms associated with this practice. Therefore, the complex mental process that

involves meditation is a fascinating field of research in progress.

However, as previously mentioned, the different studies have demonstrated that med-

itation is an active mental training, capable of modifying the functioning of the brain and

mind, favoring the attentional skills, cognitive capacity and emotional regulation. This

enables the person to respond better to day-to-day stressor stimuli. In addition, they have

confirmed the understanding that the brain is modified according to the experiences of the

individual, and support the notion that the practice of meditation may have a long-term

effect, producing lasting changes by acting on brain plasticity.

Nowadays, it is known that mental attitudes may influence the body, generating health

or diseases, to the extent that they balance or unbalance the release of innumerable hor-

mones (Danucalov and Simões 2006). Studies have confirmed the link between mental

processes and autonomic aspects relative to the functioning of the nervous system, which

cause the creation of an entirely new discipline, known as psychoneuroimmunology

(Lutgendorf and Costanzo 2003; Marques-Deak and Sternberg 2004; McnCain and Gray

2005). According to this science, a chronically altered mind may produce negative effects

on the homeostatic mechanisms of the body, facilitating the appearance of somatic diseases

(Humphreys and Lee 2009; Juster et al. 2010; Oppermann 2002). Thus, it emphasizes the

414 J Relig Health (2017) 56:411–427

123

importance of the psychological aspects to treatment or cure (Basinski et al. 2013; Bertini

et al. 2012; Pace and Heim 2011).

Therefore, meditation becomes a practice that is self-regulatory of the body and mind,

with the potential of helping a person develop the capacity to obtain some degree of control

over the psychophysiological autonomic processes. In addition, it is a means to re-establish

the organic homeostatic mechanisms, and favors cognitive and behavioral changes that

generate health and psychological well-being (Bogart 1991; Danucalov and Simões 2006;

Davidson and Goleman 1977).

According to Doctor Herbert Benson (1998), of Harvard University, who studies the

body–mind connection, emotional factors have great importance in the origin and evolu-

tion of innumerable diseases. A researcher since the 1970s about the effects of meditation

on human physiology, he affirms that persons may learn to use the mind to combat stresses

that generate physical diseases and promote health with better response to treatments

(Benson and Stark 1998).

However, in spite of the innumerable benefits pointed out, it is important to emphasize

that meditation may cause adverse effects, such depersonalization and derealization and is

therefore not indicated for individuals with borderline or psychotic conditions (Canter

2003; McGee 2008).

Over the last 30 years, meditation has been the target of innumerable researches in the

area of physical and mental health. In general, the studies suggest that the practice of

meditation, in addition to promoting self-knowledge and spiritual growth, may be an

important complementary tool to conventional treatment of different clinical conditions,

potentiating the process of cure and well-being of patients.

Researches have indicated that meditation may help to strengthen the immune system.

A study conducted in a work environment with healthy employees, vaccinated all the

individuals against influenza after 8 weeks of training in meditation. The researchers found

significant increases in the anterior activation on the left side of the frontal cortex, a pattern

previously associated with positive affections, in addition to significant increases in the

markers of antibodies for the influenza vaccine among mediators when compared with

non-meditators. This suggested that the magnitude of the increase in the activation of the

left side predicted the magnitude of the increase in the immunological response to the

influenza vaccine (Davidson 2003).

Another study verified the effect of meditation on the T CD4? lymphocytes of adults

infected with HIV-1. The T CD4? lymphocytes are the main type responsible for cell

immunity, and in patients with HIV-1 may reach a very low level, making infections more

frequent and difficult to treat. The measurements made after a period of 8 weeks training in

meditation showed that the participants of the control group presented declines in the T

CD4? lymphocyte counts, while the counts among the participants in the meditation

program remained unaltered from the beginning until the post-intervention measurement.

This effect was irrespective of the use of the antiretroviral medication. Additional analyses

demonstrated that with adhesion to the meditation program, the results indicated that a

damping effect on the reduction of T CD4? lymphocytes occurred, suggesting that the

practice may help the decline in these lymphocytes in adults infected with HIV-1 (Creswell

et al. 2009).

In this same direction, a study conducted in a school health center with a sample of

patients without any known autoimmune disturbance, investigated whether the increase in

psychosocial well-being after 8 weeks of training in meditation would be associated with

the corresponding alterations in the immunological activity markers. Analysis of the data

demonstrated that the positive improvement in psychological well-being generated by

J Relig Health (2017) 56:411–427 415

123

meditation was associated with an increase in NK cytolytic activity, and with reduction in

the levels of C-Reactive Protein (Fang and Reibel 2010).

The practice of meditation also helps to regulate arterial pressure and increase car-

diovascular efficiency. One study followed up individuals with coronary disease for a mean

period of 5.4 years and randomized the patients for inclusion in a meditation or health

education program. The study concluded that meditation significantly reduced the risk for

mortality, infarction of the myocardium and cerebral vascular accident in patients with

coronary disease. These alterations were associated with lower arterial pressure and psy-

chosocial stress factors, and therefore, the practice of meditation could be clinically useful

in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease (Schneider and Grim 2012).

In another study conducted with patients hospitalized in two health centers due to

heterogeneous diseases, one group received treatment that included daily meditations, and

the group that served as control, received only traditional treatment. Both groups were

evaluated before and after a mean period of 8 days of treatment. The results of the mea-

surements evaluated between the two groups suggested that the meditation treatment was

associated with significant improvements in the quality of life, reduction of anxiety and

control of arterial pressure (Chung et al. 2012).

Meditation has also shown an association with the quality of sleep and cognitive

function in elderly persons. A randomized controlled clinical trial evaluated elderly per-

sons who presented a reduction in sleep quality. The sleep quality and cognitive function of

the two groups were measured before the training and at the end of time intervals of 3, 6

and 12 months using four validated questionnaires. The results indicated a significant

improvement in sleep quality and cognitive functions of those who meditated when

compared with those who did not meditate (Sun et al. 2013).

Furthermore, meditation improved the emotional condition of patients with cancer.

Women recently diagnosed with breast cancer in the initial stage, who did not receive

chemotherapy, participated in a non-randomized controlled study, which used a meditation

program of 8 weeks. The results showed that the women who participated in the meditation

program had reduced the cortisol levels, improved quality of life and increased efficacy of

coping with the disease in comparison with the control group (Witek-Janusek et al. 2008).

Another study corroborated these results, evaluating 229 women after surgery,

chemotherapy and radiotherapy for stage 0 to III breast cancer. The patients were randomly

assigned to a program of 8 weeks meditation, or only to standard treatment. Evaluations as

regards mood, well-being and quality of life related to the endocrine system and breast

were made at time intervals of 0, 8 and 12 weeks. The results showed evidence that the

meditation program associated with the standard treatment helped to alleviate the physical

and emotional adverse effect of the medical treatments, including the endocrine treatments,

and these effects were maintained in the long term (Hoffman et al. 2012).

Yet another study investigated the effects of three short-term interventions on sleep and

psychological symptoms of comorbidity in cancer survivors. All the interventions, two

body–mind interventions and one educational interventions for the control group, consisted

of three sessions lasting 2 h, once a week for three consecutive weeks. The patients were

randomized and evaluated as regards sleep, quality of life, stress, depression, self-pity and

well-being. The study suggested that the two body–mind interventions were effective for

post-treatment care of sleep disturbances in these patients, and could be an ideal vehicle for

the management of multiple coexistent symptoms in cancer survivors (Nakamura et al.

2013).

Similarly, meditation has shown benefits in patients who had undergone organ trans-

plants. A randomized controlled clinical trial evaluated the efficacy of an 8-week

416 J Relig Health (2017) 56:411–427

123

meditation program in the reduction of symptoms of anxiety, depression and sleep dis-

turbances in transplant recipients. Measurements were taken at the beginning of the study,

and at time intervals of 8 weeks, 6 months and 1 year. The results showed that in the group

that meditated there was a reduction in the symptoms evaluated and improvement in

quality of life in comparison with the control group and that the benefits were maintained

throughout the course of 1 year (Gross and Kreitzer 2010).

A systematic review evaluated the efficacy of meditation in the treatment of diseases.

Studies with a healthy population were not included. Twenty randomized clinical trials

with a total of 958 individuals met the criteria. The results supported the safety and

potential efficacy of meditative practices in the treatment of epilepsy, symptoms of the

premenstrual syndrome and menopause. Benefit was also demonstrated for mood, non-

psychotic anxiety disturbances, autoimmune disease and emotional disturbances in neo-

plastic diseases (Arias and Steinberg 2006).

A meta-analysis evaluated the effects of a meditation program on stress in healthy

persons. From these studies included, with a total of 671 individuals, it was shown that the

meditation program reduced ruminative thought and trace of anxiety and increased

empathy and self-pity, and was capable of reducing stress levels in healthy persons (Chiesa

and Serretti 2009).

Another meta-analysis analyzed the effects of a meditation program on depression,

anxiety and psychological anguish in adults with different chronic somatic diseases. Eight

randomized controlled studies were included, with a total of 667 individuals, and found a

positive effect of meditation on these symptoms (Bohlmeijer et al. 2010).

Furthermore, a systematic review with meta-analysis focused specifically on the effi-

cacy of meditation for anxiety. A total of 36 randomized clinical trials were included in the

meta-analysis, with a total of 2466 observations. In 25 studies, statistically superior results

were reported in the meditation group in comparison with the control. The evaluation

demonstrated the efficacy of meditation therapies in the reduction of symptoms of anxiety.

However, it pointed out that the majority of studies measured only the improvement in the

symptoms of anxiety, but not disturbances of anxiety as clinically diagnosed (Chen and

Berger 2012).

A recent meta-analysis analyzed the efficacy of meditation programs for psychological

stress and well-being. The study included 47 clinical trials with 3515 participants suffering

from anxiety, depression, chronic pain, cancer and cardiovascular diseases, among others.

The results showed that meditation might reduce the multiple negative dimensions of

psychological stress, mainly having an effect on anxiety, depression and pain. In con-

clusion, the authors suggested that clinical physicians must be prepared to speak to their

patients about the role of meditation in mental health and stress-related behaviors (Goyal

et al. 2014).

Based on this body of scientific evidence, various hospitals and psychotherapy con-

sulting rooms in various parts of the world have associated the practice of meditation with

conventional treatments, in a complete and integral approach to the patient’s process of

cure (Davidson 2003; Hölzel et al. 2011).

In Brazil, following this world trend, since 2006 meditation has become part of the

program of National Policy of Integrative and Complementary Practices of the national

health service—SUS and has been defined as a procedure that focuses attention in a non-

analytical or discriminative manner, promoting favorable alterations in mood and cognitive

performance (Ministério da Saúde 2008).

J Relig Health (2017) 56:411–427 417

123

T a b le

1 S ci en ti fi c re se ar ch

sh o w in g ev id en ce

o f as so ci at io n b et w ee n m ed it at io n an d b en efi t in

h u m an

b o d y

A u th o r/

y ea r

T y p e o f st u d y

P o p u la ti o n

N T y p e o f

co n tr o l

T y p e o f

m ed it at io n

D u ra ti o n

O u tc o m es

an al y ze d

In st ru m en ts fo r

ev al u at in g o u tc o m e

W al la ce

(1 9 7 0 )

O p en -l ab el

u n co n tr o ll ed

cl in ic al

tr ia l

H ea lt h y

u n iv er si ty

st u d en ts w it h

p re v io u s

ex p er ie n ce

o f

m ed it at io n

1 5

– T ra n sc en d en ta l

3 0 m in

O 2 co n su m p ti o n (; )

C ar d ia c fr eq u en cy

(; )

S k in

re si st an ce

(: )

E le ct ri ca l b ra in

ac ti v it y (:

a w av es )

S p ir o m et ry

B lo o d g as o m et ry

E le ct ro ca rd io g ra p h y

G al v an o m et ry

E le ct ro en ce p h al o g ra p h y

W al la ce

et al .

(1 9 7 1 )

O p en -l ab el

co n tr o ll ed

n o n –

ra n d o m iz ed

cl in ic al

tr ia l

H ea lt h y su b je ct s

w it h p re v io u s

ex p er ie n ce

o f

m ed it at io n

3 6

S in g le –

su b je ct

(s u b je ct

as h is /h er

o w n

co n tr o l)

T ra n sc en d en ta l

2 0 – 3 0 m in

O 2 co n su m p ti o n (; )

C ar d ia c fr eq u en cy

(; )

S k in

re si st an ce

(: )

E le ct ri ca l b ra in

ac ti v it y (:

a w av es )

O 2 E li m in at io n (; )

R es p ir at o ry

q u o ti en t (N )

R es p ir at o ry

fr eq u en cy

(N )

V en ti la ti o n m in u te

(N )

A rt er ia l p re ss u re

(N )

p H

ar te ri al

(; )

P C O 2 —

ar te ri al

(N )

P O 2 —

ar te ri al

(N )

A rt er ia l la ct at e (; )

R ec ta l te m p er at u re

(N )

S p ir o m et ry

B lo o d g as o m et ry

E le ct ro ca rd io g ra p h y

G al v an o m et ry

E le ct ro en ce p h al o g ra p h y

D av id so n

(2 0 0 3 )

O p en -l ab el

co n tr o ll ed

ra n d o m iz ed

cl in ic al

tr ia l

H ea lt h y , ri g h t-

h an d ed

su b je ct s,

w it h o u t

p re v io u s

ex p er ie n ce

4 1

P as si v e

M in d fu ln es s

1 h /d ay

6 d ay /w ee k

8 w ee k s

A n x ie ty

(; )

P o si ti v e af fe ct io n (N )

N eg at iv e af fe ct io n (; )

E le ct ri ca l b ra in

ac ti v it y (:

le ft

an te ri o r ac ti v at io n )

A n ti b o d ie s fo r in fl u en za

(: )

S p ie lb er g er

S ta te -T ra it

A n xi et y In ve n to ry

P o si ti ve

a n d N eg a ti ve

A ff ec t S ca le

E le ct ro en ce p h al o g ra m

418 J Relig Health (2017) 56:411–427

123

T a b le

1 co n ti n u ed

A u th o r/

y ea r

T y p e o f st u d y

P o p u la ti o n

N T y p e o f

co n tr o l

T y p e o f

m ed it at io n

D u ra ti o n

O u tc o m es

an al y ze d

In st ru m en ts fo r

ev al u at in g o u tc o m e

T an g et

al .

(2 0 0 9 )

O p en -l ab el

co n tr o ll ed

ra n d o m iz ed

cl in ic al

tr ia l

H ea lt h y

u n iv er si ty

st u d en ts ,

w it h o u t

p re v io u s

ex p er ie n ce

8 6

A ct iv e

(r el ax at io n )

In te g ra ti v e

b o d y – m in d

tr ai n in g

2 0 m in /d ay

5 d ay s

C ar d ia c fr eq u en cy

(; )

V ar ia b il it y o f C F (: )

R es p ir at o ry

fr eq u en cy

(; )

R es p ir at o ry

am p li tu d e (: )

S k in

co n d u ct an ce

(; )

E le ct ri ca l b ra in

ac ti v it y (:

h w av es

in A C C )

A ct iv . m et ab o li c b ra in

ac ti v it y (N –

o v er al l) (:

in A C C )

E le ct ro en ce p h al o g ra p h y

S in g le -p h o to n em

is si o n

co m p u te d

to m o g ra p h y (S P E C T )

L u tz

et al .

(2 0 0 9 )

O p en -l ab el

co n tr o ll ed

n o n –

ra n d o m iz ed

cl in ic al

tr ia l

H ea lt h y

su b je ct s,

m ed it at o rs

an d

n o n –

m ed it at o rs

4 0

A ct iv e

(l es so n an d

m ed it at io n

fo r 2 0 m in )

V ip as sa n a

1 0 – 1 2 h /d ay

3 m o n th s

E le ct ri ca l b ra in

ac ti v it y (:

h w av es

in an te ri o r)

T im

e o f re ac ti o n (; )

V ar ia b il it y in

re ac ti o n ti m e (; )

T ar g et

d et ec ti o n ac cu ra cy

ra te

(: )

A tt en ti o n (: )

E le ct ro en ce p h al o g ra p h y

A tt en ti o n B li n k T a sk

D ic h o ti c L is te n in g T a sk

L u tz

et al .

( 2 0 0 4 )

C ro ss -s ec ti o n al

o b se rv at io n al

st u d y

E x p er ie n ce d

B u d d h is t

m o n k s an d

h ea lt h st u d en ts

w it h o u t

p re v io u s

ex p er ie n ce

1 8

– B u d d h is t

(u n co n d it io n a l

lo vi n g –

ki n d n es s a n d

co m p a ss io n )

– E le ct ri ca l b ra in

ac ti v it y (:

c) E le ct ro en ce p h al o g ra p h y

N ew

b er g

et al .

(2 0 0 1 )

O p en -l ab el

u n co n tr o ll ed

cl in ic al

tr ia l

H ea lt h y su b je ct s

w it h p re v io u s

ex p er ie n ce

o f

m ed it at io n

8 –

T ib et an

B u d d h is t

1 h

A ct iv . m et ab o li c b ra in

ac ti v it y (:

ci n g u la te

g y ru s, p re fr o n ta l co rt ex ,

in fe ri o r fr o n ta l an d o rb it al

an d

d o rs o la te ra l co rt ex

an d th al am

u s)

(v er ifi ca r te rm

in o lo g ia

p o r fa v o r)

S in g le -p h o to n em

is si o n

co m p u te d

to m o g ra p h y (S P E C T )

J Relig Health (2017) 56:411–427 419

123

T a b le

1 co n ti n u ed

A u th o r/

y ea r

T y p e o f st u d y

P o p u la ti o n

N T y p e o f

co n tr o l

T y p e o f

m ed it at io n

D u ra ti o n

O u tc o m es

an al y ze d

In st ru m en ts fo r

ev al u at in g o u tc o m e

S la g te r

et al .

(2 0 0 7 )

O p en -l ab el

co n tr o ll ed

n o n –

ra n d o m iz ed

cl in ic al

tr ia l

H ea lt h y

su b je ct s,

m ed it at o rs

an d

n o n –

m ed it at o rs

4 0

A ct iv e

(l es so n an d

m ed it at io n

fo r 2 0 m in )

V ip as sa n a

1 0 – 1 2 h /d ay

3 m o n th s

T ar g et

d et ec ti o n ac cu ra cy

(: )

A tt en ti o n (: )

A ll o ca ti o n o f b ra in

re so u rc es

fo r

p ri m ar y ta rg et

d et ec ti o n (; )

E le ct ro en ce p h al o g ra p h y

A tt en ti o n B li n k T a sk

K o za sa

et al .

(2 0 1 2 )

C ro ss -s ec ti o n al

o b se rv at io n al

st u d y

H ea lt h y

su b je ct s,

m ed it at o rs

an d

n o n –

m ed it at o rs

3 9

– F o cu s A tt en ti o n

an d /o r O p en

M o n it o ri n g

– A tt en ti o n (N )

Im p u ls e co n tr o l (N )

B ra in

ac ti v it y (;

in ri g h t fr o n ta l

m ed ia l, m id

te m p o ra l, p re ce n tr al

an d p o st -c en tr al

g y ri an d in

le n ti fo rm

n u cl eu s)

F u n ct io n al

n u cl ea r

m ag n et ic

re so n an ce

A ll en

et al .

(2 0 1 2 )

O p en -l ab el

co n tr o ll ed

ra n d o m iz ed

cl in ic al

tr ia l

H ea lt h y , ri g h t-

h an d ed

su b je ct s,

w it h o u t

p re v io u s

ex p er ie n ce

6 1

A ct iv e

(G ro u p

L ec tu re )

M in d fu ln es s

2 h /w ee k

6 w ee k s

C o n sc io u sn es s o f er ro rs

(N )

S ig n al

d ep en d en t o n b lo o d o x y g en

le v el

(: in

le ft p re fr o n ta l

d o rs o la te ra l co rt ex )

E rr o r- A w a re n es s T a sk

(E A T )

F u n ct io n al

n u cl ea r

m ag n et ic

re so n an ce

420 J Relig Health (2017) 56:411–427

123

T a b le

1 co n ti n u ed

A u th o r/

y ea r

T y p e o f st u d y

P o p u la ti o n

N T y p e o f

co n tr o l

T y p e o f

m ed it at io n

D u ra ti o n

O u tc o m es

an al y ze d

In st ru m en ts fo r

ev al u at in g o u tc o m e

S in g h et

al .

(2 0 1 2 )

O p en -l ab el

co n tr o ll ed

n o n –

ra n d o m iz ed

cl in ic al

tr ia l

H ea lt h y

u n iv er si ty

st u d en ts ,

w it h o u t

p re v io u s

ex p er ie n ce

3 4

S in g le –

su b je ct

(s u b je ct

as h is /h er

o w n

co n tr o l)

N o t re la te d

P h as e 1 :

D ai ly

fo r

1 m o n th

p h as e 2 :

1 5 m in

C ar d ia c fr eq u en cy

(N )

S k in

re si st an ce

(; )

sa li v ar y co rt is o l (N )

A cu te

st re ss

(; )

M em

o ry

(N )

T im

e o f re ac ti o n (; )

In te ll ig en ce

q u o ti en t (: )

E le ct ro ca rd io g ra p h y

G al v an o m et ry

S al iv ar y co rt is o l

S ta n fo rd

A cu te

S tr es s

R ea ct io n

Q u es ti o n n a ir e

(S A S R Q )

C o h en

P er ce iv ed

S tr es s

S ca le

S te rn b er g m em

o ry

te st

(M E M S C A N )

S tr o o p co lo r

in te rf er en ce

te st

In te ll ig en ce

q u o ti en t

(W ec h sl er

A d u lt

In te ll ig en ce

S ca le –

P er fo rm

a n ce

S ca le )

N . S . S ch u tt e E m o ti o n a l

In te ll ig en ce

S ca le

L az ar

et al .

(2 0 0 5 )

C ro ss -s ec ti o n al

o b se rv at io n al

st u d y

H ea lt h y

su b je ct s,

m ed it at o rs

an d

n o n –

m ed it at o rs

3 5

– In si g h t

– C o rt ic al

th ic k n es s (:

in p re fr o n ta l

co rt ex

an d ri g h t an te ri o r in su la )

N u cl ea r m ag n et ic

re so n an ce

H ö lz el

et al .

(2 0 1 1 )

O p en -l ab el

co n tr o ll ed

n o n –

ra n d o m iz ed

cl in ic al

tr ia l

H ea lt h y ri g h t-

h an d ed

su b je ct s,

m ed it at o rs

an d

n o n –

m ed it at o rs

3 5

P as si v e

M in d fu ln es s

2 .5

h /w ee k

8 w ee k s

C o n ce n tr at io n o f g ra y m at te r (:

le ft

h ip p o ca m p u s, p o st er io r ci n g u la te

co rt ex , te m p o ro p ar ie ta l ju n ct io n

an d ce re b el lu m )

N u cl ea r m ag n et ic

re so n an ce

J Relig Health (2017) 56:411–427 421

123

T a b le

1 co n ti n u ed

A u th o r/

y ea r

T y p e o f st u d y

P o p u la ti o n

N T y p e o f

co n tr o l

T y p e o f

m ed it at io n

D u ra ti o n

O u tc o m es

an al y ze d

In st ru m en ts fo r

ev al u at in g o u tc o m e

C re sw

el l

et al .

(2 0 0 9 )

U n i- b li n d

co n tr o ll ed

ra n d o m iz ed

tr ia l

H IV

? S u b je ct s

4 8

A ct iv e (1 –

d ay

se m in ar )

M in d fu ln es s

2 h /w ee k

8 w ee k s

L y m p h o cy te

co u n ts T C D 4 ?

(: )

–

F an g an d

R ei b el

(2 0 1 0 )

O p en -l ab el

co n tr o ll ed

n o n –

ra n d o m iz ed

cl in ic al

tr ia l

H ea lt h y su b je ct s

2 4

S in g le –

su b je ct

(s u b je ct

as h is /h er

o w n

co n tr o l)

M in d fu ln es s

2 .5

h /w ee k

8 w ee k s

A n x ie ty

(; )

Q u al it y o f li fe

(: )

C y to ly ti c ce ll ac ti v it y N a tu ra l-

K il le r (: )

C -R ea ct iv e p ro te in

(; )

B ri ef

S ym

p to m

In ve n to ry -1 8

M ed ic a l O u tc o m es

S u rv ey

S h o rt -F o rm

H ea lt h S u rv ey

S ch n ei d er

an d G ri m

(2 0 1 2 )

U n i- b li n d

co n tr o ll ed

ra n d o m iz ed

tr ia l

N eg ro es

w it h

co ro n al

ar te ry

d is ea se

2 0 1

A ct iv e

(H ea lt h

E d u ca ti o n )

T ra n sc en d en ta l

2 0 m in

2 ti m es /d ay

5 .4

y ea rs

C o m p o se d o f m o rt al it y b y an y

ca u se

w h at ev er

(A IM

o r C V A ) (; )

C o m p o se d o f ca rd io v as cu la r d ea th ,

re v as cu la ri za ti o n o r

ca rd io v as cu la r h o sp it al iz at io n (; )

S y st o li c b lo o d p re ss u re

(; )

P sy ch o so ci al

st re ss

fa ct o rs

(; )

C E S D

S ca le

fo r

d ep re ss io n

C o o k- M ed le y H o st il it y

In ve n to ry

A n g er

E xp re ss io n sc a le

C h u n g

et al .

(2 0 1 2 )

P ro sp ec ti v e

o b se rv at io n al

st u d y

H o sp it al iz ed

p at ie n ts

1 2 9

P as si v e

S ah aj a Y o g a

1 h

2 ti m es /d ay

8 .1

d ay s

Q u al it y o f li fe

(: )

A n x ie ty

(; )

A rt er ia l p re ss u re

(; )

A b b re v ia te d q u al it y o f

li fe

ev al u at io n

in st ru m en t

(W H O Q O L -B R E F )

W H O Q O L -S R P B

(S p ir it u al it y , R el ig io n

an d P er so n al

B el ie fs )

C li n ic a l A n xi et y S ca le

(C A S )

422 J Relig Health (2017) 56:411–427

123

T a b le

1 co n ti n u ed

A u th o r/

y ea r

T y p e o f st u d y

P o p u la ti o n

N T y p e o f

co n tr o l

T y p e o f

m ed it at io n

D u ra ti o n

O u tc o m es

an al y ze d

In st ru m en ts fo r

ev al u at in g o u tc o m e

S u n et

al .

(2 0 1 3 )

O p en -l ab el

co n tr o ll ed

ra n d o m iz ed

cl in ic al

tr ia l

T h e el d er ly

([ 6 0 y ea rs )

8 0

A ct iv e (s le ep

h y g ie n e

o n ly )

S el f- re la x at io n

an d sl ee p

h y g ie n e

3 0 m in

3 ti m es /d ay

1 y ea r

Q u al it y o f sl ee p (: )

C o g n it iv e fu n ct io n s (: )

P it ts b u rg h S le ep

Q u a li ty

In d ex

E p w o rt h S le ep in es s

S ca le

M in i M en ta l S ta te

E x am

W ec h sl er

M em

o ry

S ca le

W it ek –

Ja n u se k

et al .

(2 0 0 8 )

O p en -l ab el

co n tr o ll ed

n o n –

ra n d o m iz ed

cl in ic al

tr ia l

W o m en

w it h

ea rl y b re as t

ca n ce r

7 5

P as si v e

M in d fu ln es s

2 .5

h /w ee k

8 w ee k s

Q u al it y o f li fe

(: )

C o p in g (: )

C o rt is o l (; )

IF N -g am

a (: )

IL -4 , IL -6 , IL -1 0 (; )

C y to ly ti c ce ll ac ti v it y N a tu ra l-

K il le r (: )

Q u a li ty

o f L if e In d ex

C an ce r V er s. II I

Ja lo w ie c C o p in g S ca le

(J C S )

M in d fu l A tt en ti o n

A w a re n es s S ca le

(M A A S )

H o ff m an

et al .

(2 0 1 2 )

U n i- b li n d

co n tr o ll ed

ra n d o m iz ed

tr ia l

W o m en

w it h

S ta g e 0 – II I

b re as t ca n ce r

2 2 9

P as si v e

M in d fu ln es s

2 .5

h /w ee k

8 w ee k s

M o o d (: )

W el lb ei n g (: )

P ro fi le

o f M o o d S ta te s

(P O M S )

F u n ct io n a l A ss es sm

en t

o f C a n ce r T h er a p y—

B re a st

(F A C T -B )

F u n ct io n a l A ss es sm

en t

o f C a n ce r T h er a p y–

E n d o cr in e S ym

p to m s

(F A C T -E S )

W H O

fi ve -i te m

w el l-

b ei n g q u es ti o n n a ir e)

(W H O -5 )

N ak am

u ra

et al .

(2 0 1 3 )

O p en -l ab el

co n tr o ll ed

ra n d o m iz ed

cl in ic al

tr ia l

S u rv iv o rs

o f an y

ty p e o f ca n ce r

w it h sl ee p

d is tu rb an ce

5 7

A ct iv e (s le ep

h y g ie n e)

M in d fu ln es s e

M in d – B o d y

B ri d g in g

(M B B )

2 h /w ee k

3 w ee k s

S le ep

d is tu rb an ce

(; )

M ed ic a l O u tc o m es

S tu d y S le ep

S ca le

J Relig Health (2017) 56:411–427 423

123

T a b le

1 co n ti n u ed

A u th o r/

y ea r

T y p e o f st u d y

P o p u la ti o n

N T y p e o f

co n tr o l

T y p e o f

m ed it at io n

D u ra ti o n

O u tc o m es

an al y ze d

In st ru m en ts fo r

ev al u at in g o u tc o m e

G ro ss

an d

K re it ze r

(2 0 1 0 )

O p en -l ab el

co n tr o ll ed

ra n d o m iz ed

cl in ic al

tr ia l

S o li d o rg an

tr an sp la n t

re ci p ie n ts

1 3 8

A ct iv e

(H ea lt h

E d u ca ti o n )

M in d fu ln es s-

B a se d S tr es s

R ed u ct io n

(M B S R )

2 .5

h /w ee k

8 w ee k s

A n x ie ty

(; )

D ep re ss io n (; )

Q u al it y o f sl ee p (: )

S ta te -T ra it A n xi et y

In ve n to ry — S ta te

V er si o n (S T A I)

C en te r fo r

E p id em

io lo g ic a l

S tu d ie s -D

ep re ss io n

S ca le

(C E S -D

) P it ts b u rg h S le ep

Q u a li ty

In d ex

(P S Q I)

* (N

) w it h o u t al te ra ti o n , (: ) in cr ea se , (; ) re d u ct io n

424 J Relig Health (2017) 56:411–427

123

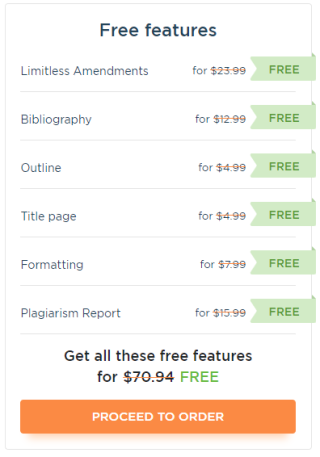

Table 1 presents a summary of the characteristics of the studies that were included in

order to demonstrate the associations between the practice of meditation and its effects on

the human body.

Conclusion

The growing scientific interest in meditation showed that this practice is a mental training

associated with lasting changes in cognition and emotion. Different methodologies have

shown that this association and its impact on self-regulation are well established. However,

the changes in physical and mental health reported in response to meditation need to be

better explored, and their impact on the brain requires further studies.

Nevertheless, the body of scientific evidence that has already been obtained with respect

to the benefits arising from meditation for the recovery of health encourage a change to

more integrated forms of treatment, and therapeutic interventions that incorporate the

practice of meditation are becoming increasingly popular.

Health begins to be understood as ample well-being that involves interaction between

the physical, emotional, mental and spiritual aspects of the individual. This new paradigm

has a concept of the human being as an indivisible whole, in which all its dimensions need

to be cared for. It emphasizes the need for a multidisciplinary approach to the patient’s

cure.

Meditation, by supporting the individual to develop his/her own resources for self-

regulation, is at present accepted within a context of integrative treatment in the area of

health.

Acknowledgments Sampaio CVS was supported by a master’s degree scholarship from Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nı́vel Superior (CAPES).

References

Allen, M., Dietz, M., Blair, K. S., van Beek, M., Rees, G., Vestergaard-Poulsen, P., et al. (2012). Cognitive- affective neural plasticity following active-controlled mindfulness intervention. The Journal of Neu- roscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 32(44), 15601–15610.

Arias, A., & Steinberg, K. (2006). Systematic review of the efficacy of meditation techniques as treatments for medical illness. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine (New York, N.Y.), 12(8), 817–832.

Basiński, A., Stefaniak, T., & Stadnyk, M. (2013). Influence of religiosity on the quality of life and on pain intensity in chronic pancreatitis patients after neurolytic celiac plexus block: Case-controlled study. Journal of Religion and Health, 52(1), 276–284.

Benson, H., & Stark, M. (1998). Medicina espiritual: o poder essencial da cura. Rio de Janeiro: Campus. Bertini, M., Conti, C., & Fulcheri, M. (2012). Psychoneuroimmunology and health psychology: Inflam-

mation and protective factors. Journal of Biological Regulators and Homeostatic Agents, 27, 637–645. Bogart, G. (1991). The use of meditation in psychotherapy: A review of the literature. American Journal of

Psychotherapy, 45(3), 383–412. Bohlmeijer, E., Prenger, R., Taal, E., & Cuijpers, P. (2010). The effects of mindfulness-based stress

reduction therapy on mental health of adults with a chronic medical disease: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 68(6), 539–544.

Canter, P. (2003). The therapeutic effects of meditation. BMJ, 326, 1049–1050. Cardoso, R., de Souza, E., Camano, L., & Leite, J. R. (2004). Meditation in health: An operational defi-

nition. Brain Research Protocols, 14(1), 58–60. Carneiro, D. (2009). Ayurveda: saúde e longevidade na tradição milenar da Índia. São Paulo: Pensamento.

J Relig Health (2017) 56:411–427 425

123

Chen, K., & Berger, C. (2012). Meditative therapies for reducing anxiety: A systematic review and meta- analysis of randomized controlled trials. Depression and Anxiety, 29(7), 545–562.

Chiesa, A., & Serretti, A. (2009). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for stress management in healthy people: A review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 15(5), 593–600.

Chung, S.-C., Brooks, M. M., Rai, M., Balk, J. L., & Rai, S. (2012). Effect of Sahaja yoga meditation on quality of life, anxiety, and blood pressure control. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 18(6), 589–596.

Creswell, J., Myers, H., Cole, S., & Irwin, M. (2009). Mindfulness meditation training effects on CD4? T lymphocytes in HIV-1 infected adults: A small randomized controlled trial. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 23(2), 184–188.

Danucalov, M., & Simões, R. (2006). Neurofisiologia da meditação. São Paulo: Phorte. Davidson, R. (2003). Alterations in brain and immune function produced by mindfulness meditation.

Psychosomatic Medicine, 66(1), 148–149. Davidson, R., & Goleman, D. (1977). The role of attention in meditation and hypnosis: A psychobiological

perspective on transformations of consciousness. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 25(4), 291–308.

Fang, C., & Reibel, D. (2010). Enhanced psychosocial well-being following participation in a mindfulness- based stress reduction program is associated with increased natural killer cell activity. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 16(5), 531–538.

Goyal, M., Singh, S., Sibinga, E. M. S., Gould, N. F., Rowland-Seymour, A., Sharma, R., et al. (2014). Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(3), 357–368.

Gross, C., & Kreitzer, M. (2010). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for solid organ transplant recipients: A randomized controlled trial. Alternative Therapies Health Medicine, 16(5), 30–38.

Hoffman, C. J., Ersser, S. J., Hopkinson, J. B., Nicholls, P. G., Harrington, J. E., & Thomas, P. W. (2012). Effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction in mood, breast- and endocrine-related quality of life, and well-being in stage 0 to III breast cancer: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 30(12), 1335–1342.

Hölzel, B. K., Carmody, J., Vangel, M., Congleton, C., Yerramsetti, S. M., Gard, T., & Lazar, S. W. (2011). Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray matter density. Psychiatry Research, 191(1), 36–43.

Humphreys, J., & Lee, K. (2009). Interpersonal violence is associated with depression and chronic physical health problems in midlife women. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 30(4), 206–213.

Juster, R.-P., McEwen, B. S., & Lupien, S. J. (2010). Allostatic load biomarkers of chronic stress and impact on health and cognition. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(1), 2–16.

Kozasa, E. H., Sato, J. R., Lacerda, S. S., Barreiros, M. A., Radvany, J., Russell, T. A., et al. (2012). Meditation training increases brain efficiency in an attention task. NeuroImage, 59(1), 745–749.

Krisanaprakornkit, T., Krisanaprakornkit, W., Piyavhatkul, N., & Laopaiboon, M. (2006). Meditation therapy for anxiety disorders. Cochrane Database System Reveiws, (1), CD004998.

Lazar, S., Kerr, C., & Wasserman, R. (2005). Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness. NeuroReport, 16(17), 1893–1897.

Lutgendorf, S. K., & Costanzo, E. S. (2003). Psychoneuroimmunology and health psychology: An inte- grative model. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 17(4), 225–232.

Lutz, A., Greischar, L. L., Rawlings, N. B., Ricard, M., & Davidson, R. J. (2004). gamma synchrony during mental practice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101(46), 16369–16373.

Lutz, A., Slagter, H. A., Dunne, J. D., & Davidson, R. J. (2008). Attention regulation and monitoring in meditation. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 12(4), 163–169.

Lutz, A., Slagter, H. A., Rawlings, N. B., Francis, A. D., Greischar, L. L., & Davidson, R. J. (2009). Mental training enhances attentional stability: Neural and behavioral evidence. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 29(42), 13418–13427.

Marques-Deak, A., & Sternberg, E. (2004). Psychoneuroimmunology: The relation between the central nervous system and the immune system. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 26(3), 143–144.

McGee, M. (2008). Meditation and psychiatry. Psychiatry (Edgmont), 5(1), 28–41. McnCain, N., & Gray, D. (2005). Implementing a comprehensive approach to the study of health dynamics

using the psychoneuroimmunology paradigm. ANS. Advances in Nurse’s Science, 28(4), 320–332. Menezes, C., Dell’Aglio, & Dalbosco, D. (2009). Os efeitos da meditação à luz da investigação cientı́fica em

Psicologia: Revisão de literatura. Psicologia: Ciência E Profissão, 29(2), 276–89.

426 J Relig Health (2017) 56:411–427

123

Menezes, C., Dell’Aglio, D., & Bizarro, L. (2011). Meditação, bem-estar ea ciência psicológica: revisão de estudos empı́ricos. Interação Em Psicologia, 15(2), 239–248.

Ministério da Saúde, S. de A. à S. (2008). Polı́tica Nacional de Práticas Integrativas e Complementares no SUS. Brası́lia.

Nakamura, Y., Lipschitz, D. L., Kuhn, R., Kinney, A. Y., & Donaldson, G. W. (2013). Investigating efficacy of two brief mind-body intervention programs for managing sleep disturbance in cancer survivors: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Journal of Cancer Survivorship: Research and Practice, 7(2), 165–182.

Newberg, A., Alavi, A., & Baime, M. (2001). The measurement of regional cerebral blood flow during the complex cognitive task of meditation: A preliminary SPECT study. Psychiatry Research: Neu- roimaging Section, 106(2), 113–122.

Oppermann, R. (2002). Efeitos do estresse sobre a imunidade ea doença periodontal. Revista Faculdade de Odontologia Porto Alegre, 43(2), 52–59.

Pace, T. W. W., & Heim, C. M. (2011). A short review on the psychoneuroimmunology of posttraumatic stress disorder: From risk factors to medical comorbidities. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 25(1), 6–13.

Schneider, R., & Grim, C. (2012). Stress reduction in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease randomized, controlled trial of transcendental meditation and health education in Blacks. Circulation Cardiovascular Quality Outcomes, 5(6), 750–758.

Servan-Shreiber, D. (2008). Anticâncer: prevenir e vencer usando nossas defesas naturais. Rio de Janeiro: Objetiva.

Singh, Y., Sharma, R., & Talwar, A. (2012). Immediate and long-term effects of meditation on acute stress reactivity, cognitive functions, and intelligence. Alternative Therapies Health Medicine, 18, 46–53.

Slagter, H. A., Lutz, A., Greischar, L. L., Francis, A. D., Nieuwenhuis, S., Davis, J. M., & Davidson, R. J. (2007). Mental training affects distribution of limited brain resources. PLoS Biology, 5(6), e138.

Sun, J., Kang, J., Wang, P., & Zeng, H. (2013). Self-relaxation training can improve sleep quality and cognitive functions in the older: A one-year randomised controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22(9–10), 1270–1280.

Tang, Y.-Y., Ma, Y., Fan, Y., Feng, H., Wang, J., Feng, S., et al. (2009). Central and autonomic nervous system interaction is altered by short-term meditation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sci- ences of the United States of America, 106(22), 8865–8870.

Wallace, R. (1970). Physiological effects of transcendental meditation. Science, 167(March), 1751–1754. Wallace, R., Benson, H., & Wilson, A. (1971). A wakeful hypometabolic physiologic state. American

Journal of Psychotherapy, 221, 795–799. Willis, R. (1979). Meditation to fit the person: Psychology and the meditative way. Journal of Religion and

Health, 18(2), 93–119. Witek-Janusek, L., Albuquerque, K., Chroniak, K. R., Chroniak, C., Durazo-Arvizu, R., & Mathews, H. L.

(2008). Effect of mindfulness based stress reduction on immune function, quality of life and coping in women newly diagnosed with early stage breast cancer. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 22(6), 969–981.

J Relig Health (2017) 56:411–427 427

123

Journal of Religion & Health is a copyright of Springer, 2017. All Rights Reserved.

- Meditation, Health and Scientific Investigations: Review of the Literature

- Abstract

- Meditation

- Meditation Recognized by Scientific Investigation as a Resource for a Healthy Life and Cure

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgments

- References

The post Meditation, Health and Scientific Investigations: Review of the Literature appeared first on Infinite Essays.

[ad_2]

Source link